On February 10, my colleague and friend from Ireland, Liz Gleeson, and I went to teach the Open Floor Movement Practice at The Good Chance Theatre, a theater space in the refugee camp called "The Jungle" in Calais. Good Chance Calais is a space where people can meet, talk, create, sing, write, dance, share their stories and find a common humanity in the midst of a devastating situation. Below are the blogs Liz posted every day on facebook, all here in one place for you to read. If you feel moved by what you read and want to help, you can find out more and donate at the following links:

Good Chance Theatre: www.goodchance.org.uk

Help Refugees: www.helprefugees.org.uk

Good Chance Theatre: www.goodchance.org.uk

Help Refugees: www.helprefugees.org.uk

Day 1

We left Paris at 9am this morning, a three hour trip to Calais in front of us. The sun was shining in the windows and I was filled with hope and optimism for what lay ahead of us. An hour into the trip, it started to snow, followed quickly by heavy rain which pelted down relentlessly for the rest of the journey. My mind immediately went to our destination The Jungle, the people there living under tarps and tents, living for months, some even years, in these conditions that were just about manageable in our cozy hire car.

We checked out the location of our accommodation and decided to drive around and get our bearings. The first thing to hit us when we arrived in Calais was the presence of so many police. Police van after police van lined the streets. It became apparent that we were nearing the camp when we started to pass hoards of young men, either walking to town or back to camp. No women, no children, just lots and lots of men. A wave of intimidation rippled through me, which I ignored. The entrance to the camp had a heavy police presence. I pulled up the hire car and jumped out to talk to them, they weren’t in the mood for a chat. “We’re going into the camp, we’re going to help out at the theatre, can you tell me where it is?” . “No, Madame”. I asked was it okay to bring in the car or should we leave it outside, “I don’t know, Madame, I don’t know what goes on in there”. “Okay, so”, I kept on with them, “is it okay to park our car here beside your van?”. “No, Madame”. I jumped back into the car and Stacey and I decided to go on in. Two other police men were just ahead of us so I thought I’d try my luck again. Initially they were as helpful as the first two, then one of them felt sorry for us and told us that cars go in and out all the time. He then wished us good luck. As we drove away, I really hoped that we wouldn’t need the luck….and we didn’t.

We drove onto a dirt track, flanked either side by vast, empty spaces. We later learnt that these had recently been bulldozed to keep residents of the Jungle from living too close to the motorway. Just past this space and the Jungle experience began. The first hut on the right hand side (made with wood and plastic sheeting) was a shop. I pulled down the window and we were greeted by a very smiley young man who put his hand into the car to shake our hands. I asked him if he knew the way to the theatre, but he didn’t understand me. “The Theatre? Good Chance? Dancing? Music?”. He shook his head, lost. I then did a little boogie with my body – “Ah, yes!”. He jumped into the back seat along with a friend – “drive, we show you”. We drove into the camp, our car parting seas of young men who were walking together, chatting, smoking, on phones. Rocks and potholes filled with water and mud were all over the path which we followed. We passed tents, make-shift shelters, caravans and works-in-progress for about 400meters – each one sitting right on top of the one before, the ‘road’ snaking among them. People looked at us, but mostly didn’t react in any particular way. There were lots of white-skinned people standing around talking to each other, many young volunteers from the UK, some there for a few weeks, others have been there for a few months, each doing whatever they can to make a difference.

Our two new friends brought us right to the theatre and then jumped out of the car, wishing us luck and off they went. It felt like a safe, hospitable and friendly environment. I felt good there, it reminded me of a trip to Morocco last year, albeit without the colour – the Jungle is very grey and colorless. We met with Amy and Benin, two British volunteers who have been managing the Good Chance Theatre. It was evident on arrival that the Theatre is a popular space – a volleyball match had just come to an end and lots of young Afghani lads were still hanging around, in good spirits from the game. They had recently been donated the volleyball net and the young men were loving this new sport. As we went in, hand after hand was thrust at us, along with names that I couldn’t pronounce and knew that I probably wouldn’t remember. They were curious about us, what we were doing here, what sort of dance were we going to offer. Before I knew it, I was standing alongside one of the men, following his steps and learning my first Afghan dance……

Another young man was standing at the side of the tent, singing. He had a beautiful, distinct voice, singing in a language that I didn’t recognize. He glanced back subtly to see if we were listening to him. Amy, our hostess, was at one side of the tent having a heart-to-heart with a young boy who couldn’t have been more than thirteen years old. He looked sad and she was giving him her full attention. I wondered about his story. When Amy was ready, we chatted about the logistics of the next few days, the times we would work, how we would work, with whom we would work. Although there are twenty or so different nationalities in the camp, the main users of the Good Chance Theatre are Afghan teenage boys.

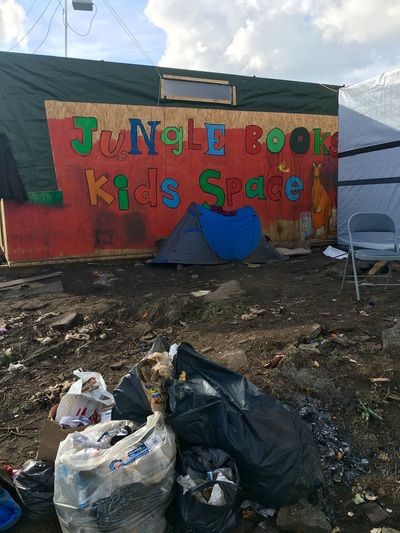

Amy and her colleague Benin invited us to dinner in one of the local Afghan restaurants. The Jungle is full of restaurants, shops, hairdressers, even a nightclub – all self-organized and set-up by the residents, sometimes with the help of volunteers.

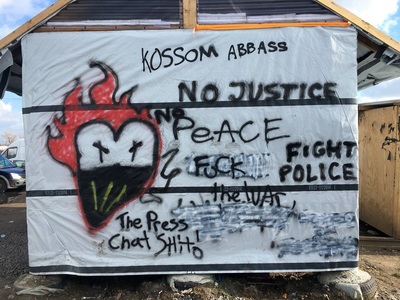

We walked past some of these shops and homes, I was trying hard not to stare or look shocked, trying to appear as though I was right at home there. But my peripheral vision was hard at work, taking it all in. The horse trough filled with water where men were cleaning their feet – perhaps getting ready to pray? The young boy, maybe ten, wearing a pink coat with fur-lined hood – who had owned that before him? Did he care that it was pink or was he just glad not to be cold? The graffiti on some of the shelters “Fuck privilege”, “Never give up”, “Open the borders”. I wondered how they felt about us privileged ones walking among their homes. I was struck by the beauty of these men, by their smiles, by the way they greeted us, by the hands of friendship that were being thrust at us whenever we encountered someone new.

Benin ordered some tea for us, along with 2 plates of spinach, 2 plates of beans, 2 plates of rice and some bread that resembled naan. The tea came, full of honey and milk – we drank it gratefully. The restaurant was quite large, bigger than many of the restaurants in my hometown of Greystones. There were groups of men sitting around, and a few young boys. One boy came up to our table to talk to Amy. His upper lip was just beginning to sprout hair; maybe fourteen years old? He was a beautiful looking child, who smiled and greeted us politely, declining Amy’s offer to join us for dinner. I wanted to ask about him, where’s his family, does he have a mother, is he here alone… so many unanswered questions. I kept quiet, not wanting to be an annoying newcomer. Apparently there are a lot of annoying newcomers, people who think they are doing good, coming in at weekends and chatting to residents, but mostly taking photos of people who don’t want to be photographed or just being voyeuristic. I checked myself for that too, more than once. Benin told us that a group of about 10 French and British volunteers had come in one weekend and didn’t talk to anyone, they set about collecting rubbish. They spent the weekend collecting rubbish and removing it from the camp. He told us that it was the single most useful act of support that he had witnessed since his arrival.

A TV was playing in a corner with a group of youths watching it. In another corner, three men were talking intently to each other, affectionately touching each others legs as they spoke. I could see nothing but community and connection everywhere I looked. Another young boy came over to our table and made a beeline for Amy. He had an iPhone in his hand and wondered if it was Amy’s – her phone had been stolen the day before, this kid had just bought the iPhone for €30 of the busy black market that opens up every evening as dusk falls. Stacey wondered if she’d be able to upgrade to an iPhone 6 for €30 and got quite excited for a few minutes.

I had expected the camp to be more dirty, more smelly than it was. There was a bit of a whiff walking past the portable toilets, but I’ve seen and smelt worse at Electric Picnic. I did see one man pissing at the side of the road – a French policeman.

We ate our dinner and thanked the chef, paying him €22 for the five of us who had eaten and drank and then Benin walked us back to our car. Back at the car, there was a group of guys, some of the ones that we had chatted to earlier. One of them looked at me and asked me to give him my passport – “I want to go to the UK” he said. I told him I’m not British, I’m Irish. “I don’t care, I’ll go to Ireland” he retorted. “I don’t think you’d get away with it” I said, “you don’t really look like me”. “I can be a woman, I can dress up”. I smiled at him, it was half a joke and half desperation. “Maybe I’ll see you tomorrow?” I said, “we’re starting at 12.00”. He looked down at his feet and responded “I didn’t come here to dance, I came here to get a life in the UK”.

We drove out of the Jungle, about 2 hours after we had gone in. Three minutes later and we were back in the centre of Calais, surrounded by opulence and privilege. The juxtaposition hit us like a ton of bricks. I asked Stacey to pass me the packet of chocolate biscuits that we had left on the back seat of the car, but they were gone. We looked at each other and laughed – “those guys took our biscuits”. But as we were closing up the car, we spotted the box under the passenger seat where it had fallen – we were humiliated and humbled in equal measure.

Tomorrow at midday, we will introduce Open Floor Movement Practice to the people of the Jungle...

We checked out the location of our accommodation and decided to drive around and get our bearings. The first thing to hit us when we arrived in Calais was the presence of so many police. Police van after police van lined the streets. It became apparent that we were nearing the camp when we started to pass hoards of young men, either walking to town or back to camp. No women, no children, just lots and lots of men. A wave of intimidation rippled through me, which I ignored. The entrance to the camp had a heavy police presence. I pulled up the hire car and jumped out to talk to them, they weren’t in the mood for a chat. “We’re going into the camp, we’re going to help out at the theatre, can you tell me where it is?” . “No, Madame”. I asked was it okay to bring in the car or should we leave it outside, “I don’t know, Madame, I don’t know what goes on in there”. “Okay, so”, I kept on with them, “is it okay to park our car here beside your van?”. “No, Madame”. I jumped back into the car and Stacey and I decided to go on in. Two other police men were just ahead of us so I thought I’d try my luck again. Initially they were as helpful as the first two, then one of them felt sorry for us and told us that cars go in and out all the time. He then wished us good luck. As we drove away, I really hoped that we wouldn’t need the luck….and we didn’t.

We drove onto a dirt track, flanked either side by vast, empty spaces. We later learnt that these had recently been bulldozed to keep residents of the Jungle from living too close to the motorway. Just past this space and the Jungle experience began. The first hut on the right hand side (made with wood and plastic sheeting) was a shop. I pulled down the window and we were greeted by a very smiley young man who put his hand into the car to shake our hands. I asked him if he knew the way to the theatre, but he didn’t understand me. “The Theatre? Good Chance? Dancing? Music?”. He shook his head, lost. I then did a little boogie with my body – “Ah, yes!”. He jumped into the back seat along with a friend – “drive, we show you”. We drove into the camp, our car parting seas of young men who were walking together, chatting, smoking, on phones. Rocks and potholes filled with water and mud were all over the path which we followed. We passed tents, make-shift shelters, caravans and works-in-progress for about 400meters – each one sitting right on top of the one before, the ‘road’ snaking among them. People looked at us, but mostly didn’t react in any particular way. There were lots of white-skinned people standing around talking to each other, many young volunteers from the UK, some there for a few weeks, others have been there for a few months, each doing whatever they can to make a difference.

Our two new friends brought us right to the theatre and then jumped out of the car, wishing us luck and off they went. It felt like a safe, hospitable and friendly environment. I felt good there, it reminded me of a trip to Morocco last year, albeit without the colour – the Jungle is very grey and colorless. We met with Amy and Benin, two British volunteers who have been managing the Good Chance Theatre. It was evident on arrival that the Theatre is a popular space – a volleyball match had just come to an end and lots of young Afghani lads were still hanging around, in good spirits from the game. They had recently been donated the volleyball net and the young men were loving this new sport. As we went in, hand after hand was thrust at us, along with names that I couldn’t pronounce and knew that I probably wouldn’t remember. They were curious about us, what we were doing here, what sort of dance were we going to offer. Before I knew it, I was standing alongside one of the men, following his steps and learning my first Afghan dance……

Another young man was standing at the side of the tent, singing. He had a beautiful, distinct voice, singing in a language that I didn’t recognize. He glanced back subtly to see if we were listening to him. Amy, our hostess, was at one side of the tent having a heart-to-heart with a young boy who couldn’t have been more than thirteen years old. He looked sad and she was giving him her full attention. I wondered about his story. When Amy was ready, we chatted about the logistics of the next few days, the times we would work, how we would work, with whom we would work. Although there are twenty or so different nationalities in the camp, the main users of the Good Chance Theatre are Afghan teenage boys.

Amy and her colleague Benin invited us to dinner in one of the local Afghan restaurants. The Jungle is full of restaurants, shops, hairdressers, even a nightclub – all self-organized and set-up by the residents, sometimes with the help of volunteers.

We walked past some of these shops and homes, I was trying hard not to stare or look shocked, trying to appear as though I was right at home there. But my peripheral vision was hard at work, taking it all in. The horse trough filled with water where men were cleaning their feet – perhaps getting ready to pray? The young boy, maybe ten, wearing a pink coat with fur-lined hood – who had owned that before him? Did he care that it was pink or was he just glad not to be cold? The graffiti on some of the shelters “Fuck privilege”, “Never give up”, “Open the borders”. I wondered how they felt about us privileged ones walking among their homes. I was struck by the beauty of these men, by their smiles, by the way they greeted us, by the hands of friendship that were being thrust at us whenever we encountered someone new.

Benin ordered some tea for us, along with 2 plates of spinach, 2 plates of beans, 2 plates of rice and some bread that resembled naan. The tea came, full of honey and milk – we drank it gratefully. The restaurant was quite large, bigger than many of the restaurants in my hometown of Greystones. There were groups of men sitting around, and a few young boys. One boy came up to our table to talk to Amy. His upper lip was just beginning to sprout hair; maybe fourteen years old? He was a beautiful looking child, who smiled and greeted us politely, declining Amy’s offer to join us for dinner. I wanted to ask about him, where’s his family, does he have a mother, is he here alone… so many unanswered questions. I kept quiet, not wanting to be an annoying newcomer. Apparently there are a lot of annoying newcomers, people who think they are doing good, coming in at weekends and chatting to residents, but mostly taking photos of people who don’t want to be photographed or just being voyeuristic. I checked myself for that too, more than once. Benin told us that a group of about 10 French and British volunteers had come in one weekend and didn’t talk to anyone, they set about collecting rubbish. They spent the weekend collecting rubbish and removing it from the camp. He told us that it was the single most useful act of support that he had witnessed since his arrival.

A TV was playing in a corner with a group of youths watching it. In another corner, three men were talking intently to each other, affectionately touching each others legs as they spoke. I could see nothing but community and connection everywhere I looked. Another young boy came over to our table and made a beeline for Amy. He had an iPhone in his hand and wondered if it was Amy’s – her phone had been stolen the day before, this kid had just bought the iPhone for €30 of the busy black market that opens up every evening as dusk falls. Stacey wondered if she’d be able to upgrade to an iPhone 6 for €30 and got quite excited for a few minutes.

I had expected the camp to be more dirty, more smelly than it was. There was a bit of a whiff walking past the portable toilets, but I’ve seen and smelt worse at Electric Picnic. I did see one man pissing at the side of the road – a French policeman.

We ate our dinner and thanked the chef, paying him €22 for the five of us who had eaten and drank and then Benin walked us back to our car. Back at the car, there was a group of guys, some of the ones that we had chatted to earlier. One of them looked at me and asked me to give him my passport – “I want to go to the UK” he said. I told him I’m not British, I’m Irish. “I don’t care, I’ll go to Ireland” he retorted. “I don’t think you’d get away with it” I said, “you don’t really look like me”. “I can be a woman, I can dress up”. I smiled at him, it was half a joke and half desperation. “Maybe I’ll see you tomorrow?” I said, “we’re starting at 12.00”. He looked down at his feet and responded “I didn’t come here to dance, I came here to get a life in the UK”.

We drove out of the Jungle, about 2 hours after we had gone in. Three minutes later and we were back in the centre of Calais, surrounded by opulence and privilege. The juxtaposition hit us like a ton of bricks. I asked Stacey to pass me the packet of chocolate biscuits that we had left on the back seat of the car, but they were gone. We looked at each other and laughed – “those guys took our biscuits”. But as we were closing up the car, we spotted the box under the passenger seat where it had fallen – we were humiliated and humbled in equal measure.

Tomorrow at midday, we will introduce Open Floor Movement Practice to the people of the Jungle...

Day 2

We started with a good breakfast and discreetly managed to slip some croissants into my laptop case for lunch. With plenty of time, we drove down Rue de Garennes towards the main entrance of the Jungle. Today, however, there was a police blockade across the entrance – looking for passports. We had left our passports at the hotel, so turned the car around. A young man approached us, looking for a lift to the train track. “Jump in”, we invited. Driving back down the long Rue de Garennes, he rolled down the window and roared out a big “hello” to several groups of his friends that we passed along the way, jeering at them that he had got a lift. “They are my friends” he said. “They WERE your friends”, I answered and we all laughed. Then the tone changed – “Can you help me get to the UK, I need to get there?”. Stacey told him that there was nothing we could do, that we would help if we could, but we simply couldn’t. He thanked us for the lift and jumped out of the car, turning to give us a thumbs-up sign.

Fifteen minutes later we were back at Rue de Garennes, passports in hand. There was a delay up ahead of us as the police thoroughly checked everyone’s passports on their system. As we waited, I spoke to the policeman who had stopped us. I asked him about his job, was it difficult for him. “Yes, it’s difficult. There are some people who have really left difficult situations behind, but there are others, bad ones, who are just taking advantage. They’re not all nice in there”. Then he got annoyed with me – “Don’t you have problems in your own country? Why do you have to come here to see our problems?”.

We eventually got in and followed the same path as yesterday. Our next hold-up was a large sanitization truck which was in the middle of the road, a man in an orange coat using a power hose to clean out the toilets. I was impressed with how thorough he was and glad that someone was doing that job. Just before 12, we arrived at the theatre and started to set-up our laptop and equipment. Very soon, a group of young men surrounded us. One small boy took over the mouse and started navigating his way with ease through my iTunes library. He was six years old, same age as my twins at home. Someone asked me if I would take him home to live with my family. I hoped so much that these kids would get out soon, and be afforded a proper life somewhere safe.

Around the edges of the dome, another fifty or so men stood or sat watching us. No matter how much we coaxed, mostly they wouldn’t budge, content to just sit and watch. Some brave souls did join us though and we started off our session with about 8 or 10 people joining us in a circle. We did some body scans, warming up the body from head to toe, slowly introducing some movement, focusing our attention in our legs and feet, using the feet as anchor. I didn’t speak their language and they didn’t speak mine, but we managed to understand each other and take cues from the body language. Twenty minutes later, we were taking turns leading the group from one side of the room to the other, taking turn leading while everyone behind imitated and followed – it was a lot of fun! Some of the younger men started taking risks, trying to get Stacey or I to imitate their very suggestive hip gestures and the men around the outside laughed when we wouldn’t do it.

We really had to think on our feet, working with this group, people coming in and out of the dome all the time. Some people game for a dance, others wanting none of it. Nobody spoke French and some had very broken English – giving instructions was going to be pointless, so we had to use our bodies to teach. We muddled through the first hour, managing to encourage the few who were dancing to keep moving and Stacey got the guys on the outside involved by clapping to the music. Then one young man arrived with his phone and asked if we would play some Afghan music that he had. This immediately brought life to the dome! Several of them took to the floor, forming a circle and finding a common rhythm. I joined them, as did a man from Eritrea and another man from Sudan. Amy was delighted, she told me that it was the first time she had seen the different nationalities dancing together. The men were really beautiful to watch as they moved, spinning their arms around, flicking their heads as they turned, a real feminine grace about their movements, which I’ve never seen in Western men. Each one seemed exceptionally handsome, their shyness making them seem quite vulnerable too. As I twirled and turned with them, following their lead, sometimes getting hit in the face by a moving arm if I went the wrong way, I really thought to myself, “Wow, this is a moment in time”. We had come to bring Open Floor Movement Practice to the refugees in the Jungle and here they were gifting us with their own dance, their own medicine.

One young boy danced with us for the whole two hours, an orange scarf in his hand which he used as a prop for his dance. He moved with such grace and ease, he was a joy to accompany on the dance floor. He was young and playful, grabbing my glasses and putting them on himself. His dance was full of sensuality, longing and soulfulness, he was so out place in this grey, desolate environment. I wondered how he kept going, how he held on to the joy. Perhaps he was new enough to the Jungle and soon would be like the men who lined the sides of the dome, sullen, withdrawn and somewhat desolate. Another Sudanese man had been hanging around at the edges of the dome. I held my hand out towards him and with a smile, he took it and joined us for an Afghan dance. Later, I sat beside him on the bench and asked if he had any Sudanese music on his phone. I watched him unlock his phone – a photo of his mother as a screensaver with the words ‘I love you’ written across the photo. He gave me his phone to play a song, it was a slow one, a gentle African rhythm. We danced to his music and I noticed how so much of the movement was in the legs and hips, really grounding, unlike the Afghan music which screeched to incredibly high pitches and often grated on the ears. After his song was over, he joined his hands together and bowed towards me, then put his hand on his heart and said ‘thank you’. He told me that he’d be back the following day with more music and his friends. At that moment, I knew that what we were doing was ‘enough’. It wasn’t quite Open Floor, but we were tuning into our group and taking our lead from them and what they needed – and that is what Open Floor is all about. As Pema Chodron says, ‘Start where you are’.

It was a long two hours for Stacey and I, we were both exhausted at the end of it. It had taken so much effort to engage the men and to try to communicate with them and encourage them to move with us. One young boy was very aggressive towards us, pretending that he was going to punch Stacey, stamping on my foot, kicking the table with our equipment on it. He was about fifteen years old and he was so ill at ease, just not okay in his skin. We later learnt that he is travelling alone and has a lot of psychological problems because of where he comes from. I left feeling disappointed that we hadn’t won him over.

After our session, we took a little walk around the camp. Today, we saw a fair few women and children. Three little ones were settling a doll into a buggy, taking care of their baby between them – they couldn’t have been more than three years old. Some older kids, maybe four or five, were playing in a makeshift playground. Kids bikes, buggies and rubbish were scattered throughout the camp in between the huts and tents and toilets. We found an Eritrean restaurant that had all the basics, like beer, wine and a selection of hookahs in many different colours. A lot of art and graffiti cover many of the wooden walls, peoples prayers for freedom, release from the jungle, love and peace.

And then we drove back to Calais, the French port town where life goes on as if there aren’t 6,000 people living on mud across the river.

Fifteen minutes later we were back at Rue de Garennes, passports in hand. There was a delay up ahead of us as the police thoroughly checked everyone’s passports on their system. As we waited, I spoke to the policeman who had stopped us. I asked him about his job, was it difficult for him. “Yes, it’s difficult. There are some people who have really left difficult situations behind, but there are others, bad ones, who are just taking advantage. They’re not all nice in there”. Then he got annoyed with me – “Don’t you have problems in your own country? Why do you have to come here to see our problems?”.

We eventually got in and followed the same path as yesterday. Our next hold-up was a large sanitization truck which was in the middle of the road, a man in an orange coat using a power hose to clean out the toilets. I was impressed with how thorough he was and glad that someone was doing that job. Just before 12, we arrived at the theatre and started to set-up our laptop and equipment. Very soon, a group of young men surrounded us. One small boy took over the mouse and started navigating his way with ease through my iTunes library. He was six years old, same age as my twins at home. Someone asked me if I would take him home to live with my family. I hoped so much that these kids would get out soon, and be afforded a proper life somewhere safe.

Around the edges of the dome, another fifty or so men stood or sat watching us. No matter how much we coaxed, mostly they wouldn’t budge, content to just sit and watch. Some brave souls did join us though and we started off our session with about 8 or 10 people joining us in a circle. We did some body scans, warming up the body from head to toe, slowly introducing some movement, focusing our attention in our legs and feet, using the feet as anchor. I didn’t speak their language and they didn’t speak mine, but we managed to understand each other and take cues from the body language. Twenty minutes later, we were taking turns leading the group from one side of the room to the other, taking turn leading while everyone behind imitated and followed – it was a lot of fun! Some of the younger men started taking risks, trying to get Stacey or I to imitate their very suggestive hip gestures and the men around the outside laughed when we wouldn’t do it.

We really had to think on our feet, working with this group, people coming in and out of the dome all the time. Some people game for a dance, others wanting none of it. Nobody spoke French and some had very broken English – giving instructions was going to be pointless, so we had to use our bodies to teach. We muddled through the first hour, managing to encourage the few who were dancing to keep moving and Stacey got the guys on the outside involved by clapping to the music. Then one young man arrived with his phone and asked if we would play some Afghan music that he had. This immediately brought life to the dome! Several of them took to the floor, forming a circle and finding a common rhythm. I joined them, as did a man from Eritrea and another man from Sudan. Amy was delighted, she told me that it was the first time she had seen the different nationalities dancing together. The men were really beautiful to watch as they moved, spinning their arms around, flicking their heads as they turned, a real feminine grace about their movements, which I’ve never seen in Western men. Each one seemed exceptionally handsome, their shyness making them seem quite vulnerable too. As I twirled and turned with them, following their lead, sometimes getting hit in the face by a moving arm if I went the wrong way, I really thought to myself, “Wow, this is a moment in time”. We had come to bring Open Floor Movement Practice to the refugees in the Jungle and here they were gifting us with their own dance, their own medicine.

One young boy danced with us for the whole two hours, an orange scarf in his hand which he used as a prop for his dance. He moved with such grace and ease, he was a joy to accompany on the dance floor. He was young and playful, grabbing my glasses and putting them on himself. His dance was full of sensuality, longing and soulfulness, he was so out place in this grey, desolate environment. I wondered how he kept going, how he held on to the joy. Perhaps he was new enough to the Jungle and soon would be like the men who lined the sides of the dome, sullen, withdrawn and somewhat desolate. Another Sudanese man had been hanging around at the edges of the dome. I held my hand out towards him and with a smile, he took it and joined us for an Afghan dance. Later, I sat beside him on the bench and asked if he had any Sudanese music on his phone. I watched him unlock his phone – a photo of his mother as a screensaver with the words ‘I love you’ written across the photo. He gave me his phone to play a song, it was a slow one, a gentle African rhythm. We danced to his music and I noticed how so much of the movement was in the legs and hips, really grounding, unlike the Afghan music which screeched to incredibly high pitches and often grated on the ears. After his song was over, he joined his hands together and bowed towards me, then put his hand on his heart and said ‘thank you’. He told me that he’d be back the following day with more music and his friends. At that moment, I knew that what we were doing was ‘enough’. It wasn’t quite Open Floor, but we were tuning into our group and taking our lead from them and what they needed – and that is what Open Floor is all about. As Pema Chodron says, ‘Start where you are’.

It was a long two hours for Stacey and I, we were both exhausted at the end of it. It had taken so much effort to engage the men and to try to communicate with them and encourage them to move with us. One young boy was very aggressive towards us, pretending that he was going to punch Stacey, stamping on my foot, kicking the table with our equipment on it. He was about fifteen years old and he was so ill at ease, just not okay in his skin. We later learnt that he is travelling alone and has a lot of psychological problems because of where he comes from. I left feeling disappointed that we hadn’t won him over.

After our session, we took a little walk around the camp. Today, we saw a fair few women and children. Three little ones were settling a doll into a buggy, taking care of their baby between them – they couldn’t have been more than three years old. Some older kids, maybe four or five, were playing in a makeshift playground. Kids bikes, buggies and rubbish were scattered throughout the camp in between the huts and tents and toilets. We found an Eritrean restaurant that had all the basics, like beer, wine and a selection of hookahs in many different colours. A lot of art and graffiti cover many of the wooden walls, peoples prayers for freedom, release from the jungle, love and peace.

And then we drove back to Calais, the French port town where life goes on as if there aren’t 6,000 people living on mud across the river.

Day 3

We were braver and better prepared today, we managed to steal an entire baguette from the breakfast buffet, along with a selection of cheeses, meats and fruit. Stacey had organized a bag specifically for this purpose, so we didn’t have to fill my laptop case with food again. We headed off in the car, definitely more subdued than previous days, knowing that we had some hard work ahead of us. The police stopped us once again, checking our passports. The police at the entrance to the jungle wear a lot of armour on their clothes – big padded shoulders and arms – they look like terminators. The two who stopped us today were friendly and kind, one joking with the other that he felt like an idiot using the walkie-talkie and wanting his friend to do that. Driving through the same road as we had done on previous days, Stacey and I agreed that it really was such a dismal place – grey, black, wet, muddy – with just flickers of colourful hope every now and again, where someone’s art suggested a better reality to come. When we arrived into the theatre, there were a group of men and boys sitting around a heater. They had removed their boots and were trying to dry them out in front of the heat. The first person up to me was the boy from yesterday, who had been aggressive. I found out his name and his age – actually he’s only 12, not fifteen as I had guessed. I needed to set up the table and I asked him to help me, which he willingly did. Today, I won him over and we are friends.

We brought an orange from the breakfast table and used this to get some games going. We played a name game, throwing the orange around in the circle – it went well for some time. One young man really wanted to dance, so we let him lead us to screechy Afghan music, back and forth across the room as we followed, imitating his hand gestures and his steps. The outskirts of the circle started filling up with lots of people, all very willing to be spectators, but too shy, too reserved to move with us. Some of them had a flicker in the eye that told me there was a potential dancer inside, others had just gone through too much for it to be a consideration at this time.

There was a new boy in the theatre today. He was dressed in some sort of armour that resembled a black ninja turtle. He danced and moved and ran in between us, full of energy. But that kid needed so much more than dance, he needed a punch bag, he needed to scream, he needed to be lanced – so much anger inside him that he could barely contain it. At one point, he asked me to knock against him with my body, which I did. I banged against him as he banged against me, this went on for some time, until my arm had had enough and I drew it to an end. He was annoyed about this and kicked me as he walked off. He threw a punch at someone else as he left the theatre. The people in the Jungle are having to learn so much about containment.

As we moved in the centre of the theatre, doing our very best to encourage onlookers to come and join us, there were quite a few scuffles going on – three different fights in the space of about 30 minutes. We learnt that the French police had announced that 1,000 people are to be evicted from the Jungle in the coming week and this has caused much tension and fear among the residents. I’m not quite sure what this means – where the hell do they go?

Then Amy arrived in breathless, apologizing for having been missing, but someone’s home had caught fire and she was involved with helping to control the blaze. The smell of the burning home was wafting into the theatre as we danced around in circles to the same Afghan song, over and over again “Armani, Armani, Armani, Armani”: clap, spin to the right, spin to the left, clap, clap, turn. I thought to myself if I spin anymore, I’m going to throw up, but I kept going and I didn’t throw up and soon found myself quite enjoying the rhythmic repetition. Then a new man joined us. He was disheveled and unshaved, his clothes were filthy and I thought by the look on his face that he was either drunk or on drugs. As his two friends dragged him into the circle and thrust him towards the other dancers, I found myself constricting in my body. And then he started to move, dancing in the circle with the same grace and dedication as the others, a look of utter yearning on his face as he moved to long- forgotten music from his long-forgotten homeland. I hated myself in that moment, for having judged him at first. The more I watched the faces of these brave souls as they moved around and around together dancing to each others music, accepting each others cultures, supporting each other, encouraging each other, the smaller and smaller I felt. They have so much to teach us here.

After an hour or so, we had to shut down the music to respect the Muslim prayer time. All the nationalities reminded us that this was prayer time and we needed to respect this. I was impressed how all religions tolerated this interruption out of respect for their muslim friends. Stacey and I were glad of a break, we happily sat in the theatre for an hour while we waiting for prayer time to come to an end. It was such an effort to keep everyone engaged and moving with us. Stacey told me that she had a pain in her face from ‘fake smiling’ and I told her that I thought that’s what had given me a mirgraine the previous day – keeping up the smiles and appearances while sweating inside, wondering what the fuck we really have to offer these people? Neither of us have ever met with such resistence and such willing participation all at once. During the break, we spoke with some of the men in the space. There was quite a nice conversation happening around the fire until one man decided it was a good idea to grab my ass. I left that conversation but it did leave me wondering about the safety of the jungle for the women and the young people there. That’s why they tend to stay at home or in the women and childrens centre, where they are safe. Another man from Afghanistan told me that he had been living in the UK and has an Indian girlfriend and a three-year old child there. He was working in a pizzeria in Birmingham and had stolen £50 and was caught. Now he couldn’t get back into the UK. He asked me if it were easy to get into the UK from Ireland, if he could take a coach from Belfast or a boat to Liverpool and do the police there check passports? Life is on pause for all of these people as they dream of freedom on the other side of the English channel.

Our Sudanese men from the day before returned and were much quicker to take to the dance floor today. They were happy and smiling – Stacey had downloaded a bunch of Sudanese music which we played for them. It was a relief to dance to the slow, steady rhythm of the african music as all the Afghan spinning was making me feel quite dizzy and unsteady! Before leaving, one of the men asked for an Open Floor t-shirt, and with much embarrassment, asked us if by any chance we could pick him up a pair of shoes in size 42, “no problem if you can’t”. I could tell that this man didn’t usually ask for much and that this was taking a lot of courage on his part. I could quite easily imagine this man in a doctors white coat, helping to deliver a baby in our local maternity hopsital, he was so kind, so well dressed, so well spoken. We’ll shortly go for a drive to find a shoe shop for our friend, it will give me some relief from the total anguish, frustration and hopelessness that I feel on behalf of these people who need and deserve so much more.

Feeling today like such a tiny, miniscule, insignificant drop in a very large ocean, Stacey and I with pains on our faces from ‘fake smiling’

We brought an orange from the breakfast table and used this to get some games going. We played a name game, throwing the orange around in the circle – it went well for some time. One young man really wanted to dance, so we let him lead us to screechy Afghan music, back and forth across the room as we followed, imitating his hand gestures and his steps. The outskirts of the circle started filling up with lots of people, all very willing to be spectators, but too shy, too reserved to move with us. Some of them had a flicker in the eye that told me there was a potential dancer inside, others had just gone through too much for it to be a consideration at this time.

There was a new boy in the theatre today. He was dressed in some sort of armour that resembled a black ninja turtle. He danced and moved and ran in between us, full of energy. But that kid needed so much more than dance, he needed a punch bag, he needed to scream, he needed to be lanced – so much anger inside him that he could barely contain it. At one point, he asked me to knock against him with my body, which I did. I banged against him as he banged against me, this went on for some time, until my arm had had enough and I drew it to an end. He was annoyed about this and kicked me as he walked off. He threw a punch at someone else as he left the theatre. The people in the Jungle are having to learn so much about containment.

As we moved in the centre of the theatre, doing our very best to encourage onlookers to come and join us, there were quite a few scuffles going on – three different fights in the space of about 30 minutes. We learnt that the French police had announced that 1,000 people are to be evicted from the Jungle in the coming week and this has caused much tension and fear among the residents. I’m not quite sure what this means – where the hell do they go?

Then Amy arrived in breathless, apologizing for having been missing, but someone’s home had caught fire and she was involved with helping to control the blaze. The smell of the burning home was wafting into the theatre as we danced around in circles to the same Afghan song, over and over again “Armani, Armani, Armani, Armani”: clap, spin to the right, spin to the left, clap, clap, turn. I thought to myself if I spin anymore, I’m going to throw up, but I kept going and I didn’t throw up and soon found myself quite enjoying the rhythmic repetition. Then a new man joined us. He was disheveled and unshaved, his clothes were filthy and I thought by the look on his face that he was either drunk or on drugs. As his two friends dragged him into the circle and thrust him towards the other dancers, I found myself constricting in my body. And then he started to move, dancing in the circle with the same grace and dedication as the others, a look of utter yearning on his face as he moved to long- forgotten music from his long-forgotten homeland. I hated myself in that moment, for having judged him at first. The more I watched the faces of these brave souls as they moved around and around together dancing to each others music, accepting each others cultures, supporting each other, encouraging each other, the smaller and smaller I felt. They have so much to teach us here.

After an hour or so, we had to shut down the music to respect the Muslim prayer time. All the nationalities reminded us that this was prayer time and we needed to respect this. I was impressed how all religions tolerated this interruption out of respect for their muslim friends. Stacey and I were glad of a break, we happily sat in the theatre for an hour while we waiting for prayer time to come to an end. It was such an effort to keep everyone engaged and moving with us. Stacey told me that she had a pain in her face from ‘fake smiling’ and I told her that I thought that’s what had given me a mirgraine the previous day – keeping up the smiles and appearances while sweating inside, wondering what the fuck we really have to offer these people? Neither of us have ever met with such resistence and such willing participation all at once. During the break, we spoke with some of the men in the space. There was quite a nice conversation happening around the fire until one man decided it was a good idea to grab my ass. I left that conversation but it did leave me wondering about the safety of the jungle for the women and the young people there. That’s why they tend to stay at home or in the women and childrens centre, where they are safe. Another man from Afghanistan told me that he had been living in the UK and has an Indian girlfriend and a three-year old child there. He was working in a pizzeria in Birmingham and had stolen £50 and was caught. Now he couldn’t get back into the UK. He asked me if it were easy to get into the UK from Ireland, if he could take a coach from Belfast or a boat to Liverpool and do the police there check passports? Life is on pause for all of these people as they dream of freedom on the other side of the English channel.

Our Sudanese men from the day before returned and were much quicker to take to the dance floor today. They were happy and smiling – Stacey had downloaded a bunch of Sudanese music which we played for them. It was a relief to dance to the slow, steady rhythm of the african music as all the Afghan spinning was making me feel quite dizzy and unsteady! Before leaving, one of the men asked for an Open Floor t-shirt, and with much embarrassment, asked us if by any chance we could pick him up a pair of shoes in size 42, “no problem if you can’t”. I could tell that this man didn’t usually ask for much and that this was taking a lot of courage on his part. I could quite easily imagine this man in a doctors white coat, helping to deliver a baby in our local maternity hopsital, he was so kind, so well dressed, so well spoken. We’ll shortly go for a drive to find a shoe shop for our friend, it will give me some relief from the total anguish, frustration and hopelessness that I feel on behalf of these people who need and deserve so much more.

Feeling today like such a tiny, miniscule, insignificant drop in a very large ocean, Stacey and I with pains on our faces from ‘fake smiling’

Day 4

And today was a whole new experience. After a rough night, Stacey had to come to a really difficult decision not to join me in the Jungle today. She was full of a cold and chest infection, which I had been generously sharing with her all week and her body had finally succumbed. I drove off alone, unsure what the afternoon would bring. We were scheduled later than usual today, as there was a visiting theatre group from Wales coming to perform their play at the theatre. I arrived into Good Chance at 2pm, my rucksack with laptop and speakers on my back, unsure if I would need them today. I knew that time was tight, because of the visiting play and they might need to give the time afterwards to another visiting drama group. I was ready to Open the Floor if needed, I was also ready (and pretty willing) to step aside for someone else, if that’s what was called for. A few people had gathered on the make-shift benches as I came in. Eyes greeted mine, smiles were sent in my direction. A few men came up to me and asked if we’d be dancing later, “hey, you’re back, good to see you”. The men who had been dancing with Stacey and I on the previous days were genuinely happy to see me and sat down beside me to watch the drama. “We dance Open Floor after?”. I felt a huge swell of emotion rise up inside me which I quickly swallowed down, raising my eyes up to the roof in the hope that gravity would bring the newly emerging tears back down where they were coming from. We’ve done more than enough, I thought to myself.

I settled in to watch the play, ‘Scattered’, about a young Syrian Asylum seeker and his new found friend in Wales. https://youtu.be/zEPPoeDRFNQ Usually performed around Wales in schools, this was a very poignant audience for them. The Syrian boy, telling stories of his family divested by war, all dead now except his mother. The Welsh boy, telling the story of his parents imminent separation and the devastation that this was causing him. I scanned the room, watching the faces watching the actors, this was far-reaching for all of us gathered there. When the play had ended, I had a few words with the English director who had brought the play there. He was deeply moved to have watched his art performed for this audience, he was searching for words to tell me how this had been for him. They had brought some bunting from the UK, made by children from several schools, each triangle with a message of hope for the people in the Jungle – you’ll see the bunting in my photographs.

There was a lot of chatter and games in the theatre as the play finished. Amy asked me what was my plan for the day and I told her that I was happy to lead more Open Floor, or okay to stand aside too, if they needed the time for another group. One of the Sudanese men had invited me to see his home and have a coffee with him, so I told Amy I’d come back in 20 minutes and see what she wanted to do for the afternoon. Myself and Maki headed off through the southern part of the jungle, past the women and children’s centre, the church, the mosque, the school and the bookshop – all the places that are due to be bulldozed next week. After a few minutes, I heard someone call after me, it was Amy. “come back”, she was calling, “they’re all asking for the dance!”. I turned to Maki and smiled – “We’ll do coffee later, okay?”. I felt so good that they wanted more Open Floor, more dance. I felt that all the money we had raised from our friends and colleagues was all worthwhile and that our offering was making a difference, however small and transient.

So we set-up the music and got started. Many of the men asked where Stacey was and when I told them that she was sick, they stood in to help me out. One of them took over the DJ station, taking care of my laptop and the speakers. Another took my phone from me and said he’d shoot video and take photos. We were a community today, all of us doing our thing and supporting each other. As we began, there were more people dancing in the centre of the room than sitting on the outside – Hurray! We danced and danced and danced. Today, they were tolerating the western music much more. Many European volunteers were coming into the space to check out the session and I explained to my largely Afghan friends that we had to include them and they obliged. We had westerners dancing to Afghan traditional music, we had Sudanese, Iranian and Egyptian men join us for a rendition of ‘Black Betty’. Many of the men from previous days came and a whole new group were there too, lots of young people and some Arabs too. At one stage I was dancing with a young boy, both of us giving it socks, when a knife came tumbling out from beneath his jacket – “good to be prepared” I said, and we both laughed, as he picked it up and tucked it away underneath his clothes again. This is just the way that life is in the jungle.

I was wishing that Stacey was here to see this, everyone moving today without inhibitions, really enjoying the space. I knew that it wouldn’t have been like this without the painstaking groundwork that we had both put in during the previous days. As each song came to an end, there was the usual scuffle of about 10 people around my laptop, each of them thrusting their phone at me to play their favorite song. I’d plug in the phone and the group would respond by dancing or grabbing the phone off the cable and putting another one in. I was braver today and made them wait their turn, making sure to play music that was appealing to the other cultures present in the dome. They still managed to play ‘Armani, Armani, Armani’ at least twice during the three hours that we danced today. It reminded me of a working with a little boy who had autism, several years ago. I had played Norah Jones' "Come away with me" during our first session together and for every session afterwards, he wanted that song. The familiarity and repetition gave him much-needed comfort and containment. I wondered if the same was happening here in the theatre with the repetition of this song?

Just after six, it was time to end. It had gone so well, I was happy to leave on such a high note. “One more, one more, one more” they all called. “Okay”, I said, “one more, but this one will be from MY country and I want you all to dance with me!” I did a quick search and the first Irish song that I came across was ‘she moved through the fair’. A group gathered in a circle, first ten then fifteen, then twenty. We shuffled and swayed and moved to the gentle tones, people taking it in turns to move into the centre and offer a dance of gratitude for being able to dance here together like this. I felt so deeply moved and grateful as I watched these beautiful connections and sense of belonging unfold before me, so intrinsic to Open Floor and what it’s all about.

It was getting dark, I had promised to have a coffee with Maki and I was aware that Stacey was back at the hotel unwell. I literally had to grab my speakers off the guys who didn’t want me to leave “more dance, more dance”. After packing everything back in the car, Maki and I took off towards his home. I had 6 brand new thermal vests tucked under my arm which my friend Barbara had given to me to bring over. As we walked through and around the thick muck (it had been raining all day) we passed a little girl, about 7 years old. Maki told me that I should give them to her as she stays with several women. I handed them to her and her face lit up – “give them to your Mama” I told her. She ran off in the direction of her house, delighted with herself. As Maki and I balanced to keep ourselves on the banks at the sides of the puddles, a little toddler came towards us, right through the centre of the large puddle, kicking up the water with her boots. Maki and I laughed at her freedom, “just like my kids, I laughed”.

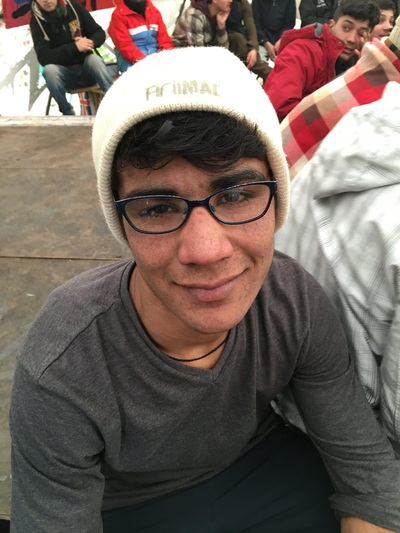

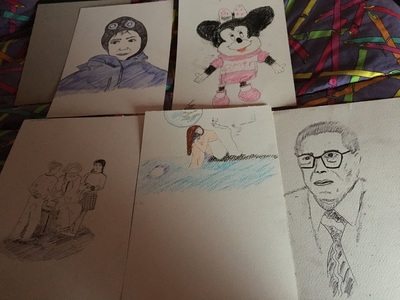

It was surreal, going into Maki’s home – a 2m x 1.5m wooden box, covered in black plastic. Inside, the walls were lined with duvets and blankets and even some colorful bunting – it was so cozy! There was just enough room for two single beds, a box in between them and a suitcase shoved down the end of one of the beds. He had lit some candles and had hot coffee ready for me in a flask. He seemed really happy to have a visitor in his home and I felt so privileged to be invited in. Maki poured me a coffee and began to tell me about his life in Sudan, how he had made it to Libya, spent 18months there before going to Italy and from there to France, where everyone believed they would make it across to the UK and find a better life for themselves. He showed me some of his drawings in his sketch book. “Can I tell people about this Maki? Can I take your photo and share your story?”. “Yes, share”. He said that it was good to have the theatre, it was good to have the dance, “thank you for bringing yourself, for coming here and dancing with us” he said that the dance had helped him to keep a light shining inside, “because it’s hard, you know, to keep that light shining”.

Epilogue

Amy arrived at the door to Maki’s house looking for me, her tires had been slashed again and she needed a car jack. In the end, I gave Amy a lift back to her campsite to pick up her car jack. I got to spend 30 minutes with this incredible young lady. Amy works at the Good Chance Theatre as a volunteer – Front of House, so to speak, she has been with them from the beginning. Over our time there, Amy was always checking in with us, making sure that we were okay, that we had everything we needed, reassuring us that we were doing a good job. I watched her interact with the men each day, joking with them, listening to them, setting boundaries when boundaries were needed, overflowing with compassion when that was called for. Nothing was beyond her, she stood her ground, encouraged everyone to participate and participated herself when she felt that this would help to break the ice – we literally couldn’t have done it without her. She was clear, compassionate, resonated with huge levels of emotional intelligence and not once, did I spot a trace of ego about her or her work. Amy is eighteen years old, she left school a few months ago and will study English literature in University College London from next September. The world needs more Amy’s. We need people like Amy to be the decision makers and the policy makers of the future. I hope that Amy’s parents and family and friends know how wonderful this young woman is!

I settled in to watch the play, ‘Scattered’, about a young Syrian Asylum seeker and his new found friend in Wales. https://youtu.be/zEPPoeDRFNQ Usually performed around Wales in schools, this was a very poignant audience for them. The Syrian boy, telling stories of his family divested by war, all dead now except his mother. The Welsh boy, telling the story of his parents imminent separation and the devastation that this was causing him. I scanned the room, watching the faces watching the actors, this was far-reaching for all of us gathered there. When the play had ended, I had a few words with the English director who had brought the play there. He was deeply moved to have watched his art performed for this audience, he was searching for words to tell me how this had been for him. They had brought some bunting from the UK, made by children from several schools, each triangle with a message of hope for the people in the Jungle – you’ll see the bunting in my photographs.

There was a lot of chatter and games in the theatre as the play finished. Amy asked me what was my plan for the day and I told her that I was happy to lead more Open Floor, or okay to stand aside too, if they needed the time for another group. One of the Sudanese men had invited me to see his home and have a coffee with him, so I told Amy I’d come back in 20 minutes and see what she wanted to do for the afternoon. Myself and Maki headed off through the southern part of the jungle, past the women and children’s centre, the church, the mosque, the school and the bookshop – all the places that are due to be bulldozed next week. After a few minutes, I heard someone call after me, it was Amy. “come back”, she was calling, “they’re all asking for the dance!”. I turned to Maki and smiled – “We’ll do coffee later, okay?”. I felt so good that they wanted more Open Floor, more dance. I felt that all the money we had raised from our friends and colleagues was all worthwhile and that our offering was making a difference, however small and transient.

So we set-up the music and got started. Many of the men asked where Stacey was and when I told them that she was sick, they stood in to help me out. One of them took over the DJ station, taking care of my laptop and the speakers. Another took my phone from me and said he’d shoot video and take photos. We were a community today, all of us doing our thing and supporting each other. As we began, there were more people dancing in the centre of the room than sitting on the outside – Hurray! We danced and danced and danced. Today, they were tolerating the western music much more. Many European volunteers were coming into the space to check out the session and I explained to my largely Afghan friends that we had to include them and they obliged. We had westerners dancing to Afghan traditional music, we had Sudanese, Iranian and Egyptian men join us for a rendition of ‘Black Betty’. Many of the men from previous days came and a whole new group were there too, lots of young people and some Arabs too. At one stage I was dancing with a young boy, both of us giving it socks, when a knife came tumbling out from beneath his jacket – “good to be prepared” I said, and we both laughed, as he picked it up and tucked it away underneath his clothes again. This is just the way that life is in the jungle.

I was wishing that Stacey was here to see this, everyone moving today without inhibitions, really enjoying the space. I knew that it wouldn’t have been like this without the painstaking groundwork that we had both put in during the previous days. As each song came to an end, there was the usual scuffle of about 10 people around my laptop, each of them thrusting their phone at me to play their favorite song. I’d plug in the phone and the group would respond by dancing or grabbing the phone off the cable and putting another one in. I was braver today and made them wait their turn, making sure to play music that was appealing to the other cultures present in the dome. They still managed to play ‘Armani, Armani, Armani’ at least twice during the three hours that we danced today. It reminded me of a working with a little boy who had autism, several years ago. I had played Norah Jones' "Come away with me" during our first session together and for every session afterwards, he wanted that song. The familiarity and repetition gave him much-needed comfort and containment. I wondered if the same was happening here in the theatre with the repetition of this song?

Just after six, it was time to end. It had gone so well, I was happy to leave on such a high note. “One more, one more, one more” they all called. “Okay”, I said, “one more, but this one will be from MY country and I want you all to dance with me!” I did a quick search and the first Irish song that I came across was ‘she moved through the fair’. A group gathered in a circle, first ten then fifteen, then twenty. We shuffled and swayed and moved to the gentle tones, people taking it in turns to move into the centre and offer a dance of gratitude for being able to dance here together like this. I felt so deeply moved and grateful as I watched these beautiful connections and sense of belonging unfold before me, so intrinsic to Open Floor and what it’s all about.

It was getting dark, I had promised to have a coffee with Maki and I was aware that Stacey was back at the hotel unwell. I literally had to grab my speakers off the guys who didn’t want me to leave “more dance, more dance”. After packing everything back in the car, Maki and I took off towards his home. I had 6 brand new thermal vests tucked under my arm which my friend Barbara had given to me to bring over. As we walked through and around the thick muck (it had been raining all day) we passed a little girl, about 7 years old. Maki told me that I should give them to her as she stays with several women. I handed them to her and her face lit up – “give them to your Mama” I told her. She ran off in the direction of her house, delighted with herself. As Maki and I balanced to keep ourselves on the banks at the sides of the puddles, a little toddler came towards us, right through the centre of the large puddle, kicking up the water with her boots. Maki and I laughed at her freedom, “just like my kids, I laughed”.

It was surreal, going into Maki’s home – a 2m x 1.5m wooden box, covered in black plastic. Inside, the walls were lined with duvets and blankets and even some colorful bunting – it was so cozy! There was just enough room for two single beds, a box in between them and a suitcase shoved down the end of one of the beds. He had lit some candles and had hot coffee ready for me in a flask. He seemed really happy to have a visitor in his home and I felt so privileged to be invited in. Maki poured me a coffee and began to tell me about his life in Sudan, how he had made it to Libya, spent 18months there before going to Italy and from there to France, where everyone believed they would make it across to the UK and find a better life for themselves. He showed me some of his drawings in his sketch book. “Can I tell people about this Maki? Can I take your photo and share your story?”. “Yes, share”. He said that it was good to have the theatre, it was good to have the dance, “thank you for bringing yourself, for coming here and dancing with us” he said that the dance had helped him to keep a light shining inside, “because it’s hard, you know, to keep that light shining”.

Epilogue

Amy arrived at the door to Maki’s house looking for me, her tires had been slashed again and she needed a car jack. In the end, I gave Amy a lift back to her campsite to pick up her car jack. I got to spend 30 minutes with this incredible young lady. Amy works at the Good Chance Theatre as a volunteer – Front of House, so to speak, she has been with them from the beginning. Over our time there, Amy was always checking in with us, making sure that we were okay, that we had everything we needed, reassuring us that we were doing a good job. I watched her interact with the men each day, joking with them, listening to them, setting boundaries when boundaries were needed, overflowing with compassion when that was called for. Nothing was beyond her, she stood her ground, encouraged everyone to participate and participated herself when she felt that this would help to break the ice – we literally couldn’t have done it without her. She was clear, compassionate, resonated with huge levels of emotional intelligence and not once, did I spot a trace of ego about her or her work. Amy is eighteen years old, she left school a few months ago and will study English literature in University College London from next September. The world needs more Amy’s. We need people like Amy to be the decision makers and the policy makers of the future. I hope that Amy’s parents and family and friends know how wonderful this young woman is!

On a personal note...This experience was one of the most challenging experiences of my life, and I wouldn't trade it for the world. I've been affected in a deep and profound way by the experience. It's been an emotional few days...once I left Calais and didn't have to hold it together anymore, the tears came and came and came. And I can't stop thinking about the fact that all those people we were with are being evicted and that area will be bulldozed in a week's time. Having been there on the ground, looking into these people's eyes, it's just way more real than when you see it on the news. So grateful to have been able to be there and help bring some light in whatever small way we might have done so.

I really encourage you to take action and give a little if you feel moved by what's been written here. Again, here are the links where you can help:

Good Chance Theatre: www.goodchance.org.uk

Help Refugees: www.helprefugees.org.uk

Thank you.

Stacey

I really encourage you to take action and give a little if you feel moved by what's been written here. Again, here are the links where you can help:

Good Chance Theatre: www.goodchance.org.uk

Help Refugees: www.helprefugees.org.uk

Thank you.

Stacey